Genotype? Phenotype? What’s my “type” anyway? Breeding for resilience when every gene matters.

Everyone knows Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn. If you’re in Alberta, you probably tack on other seasons like Mud, Bugs, Fire/Smoke, Harvest. They’re all part of the calendar and if you spend any time outside, chances are you build schedules around the seasons.

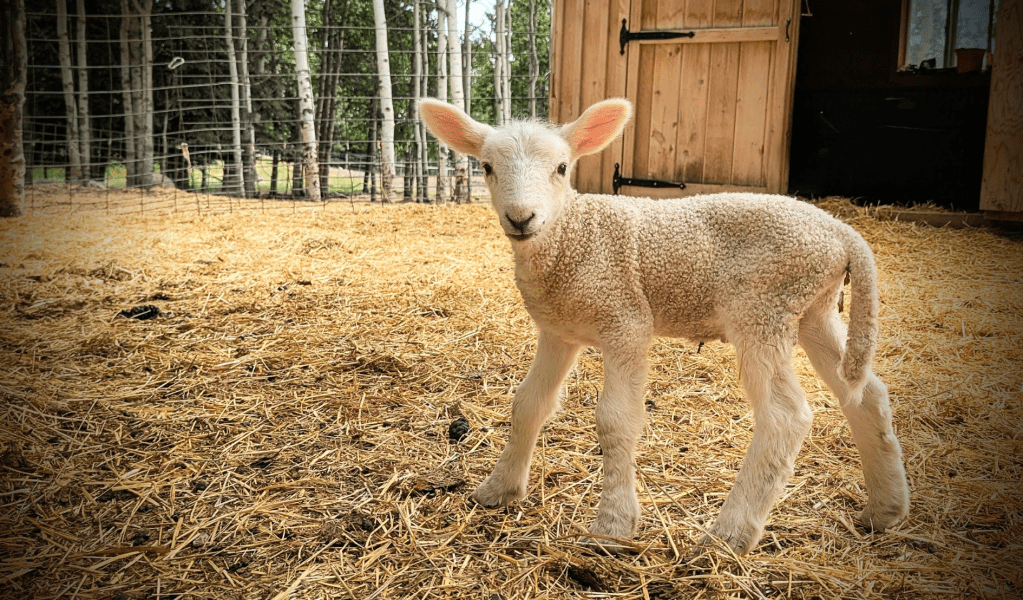

Here at the homestead, we have two more seasons we add – Breeding and Lambing. Like every livestock farmer, our world pretty much shuts down for these seasons. We don’t go anywhere, we don’t take on extra work, we sleep when we can. These seasons are consuming.

Breeding season for us usually happens somewhere in November and December. Border Leicester ewes are seasonal breeders – that means that only when the daylight hours are shorter do the ladies start to cycle. I can always tell when it’s started thanks to a lot of ivory-skulled, hormonal behaviour – the ladies get antsy and Banjo is completely distracted, hustling around his harem and sniffing behinds.

But it’s also a time to get super-practical. If breeding plans are going ahead, it’s the time to think about gates, panels and hot fences. There is feed to consider, long-range planning (150 days to due date), shearing, vaccinations and other logistics to get in place. It’s the most unromantic planning possible but every bit of it is absolutely essential – believe me, I’ve done the “by accident” route (both in the flock and in life and while I’m delighted by the outcome in both cases, it was not an experience I’d care to repeat) and planning is better.

And in the case of a rare breed or a breed that’s under conservation watch – as the Border Leicester is – breeding also represents a pivot point. When the planning is all done and the ram goes in, my flock of Border Leicesters goes from a group of sheep to a future. It’s in breeding that we make decisions that shape wool, temperament, feet health, maternal ability, survival, resilience – for a breed with a limited available gene pool, this is the time that shapes whether the breed itself stays secure.

This is stewardship in the straw.

So what are some of the thing that we’re thinking about? There are two terms that pretty quickly become mighty important – genotype and phenotype.

A phenotype is simply the collection of traits you can see – things like an animal size, the fleece colour and quality, body condition and conformation, how they move, their temperament. A genotype is the stuff that you can’t see as well – the heritable traits that an animal carries under the surface, the things that may be passed down, expressed or hidden, dominant or recessive. Phenotypes are a little like going to an open house when you’re in the market – you can see the layout, get an idea of the orientation, give the toilet handle an experimental jiggle. It tells you what’s going on RIGHT NOW with that animal. The genotype, on the other hand, is what you find when you decide to renovate – what the walls were hiding, what was under the carpet. When breeding has been done thoughtfully and conscientiously, when you lift the carpet you may find meticulous hardwood floors or a stained glass window unaccountably hidden behind the drywall. That’s the best-case scenario. Phenotype tells you what’s true right now. Genotype asks what will the lambs become in the future?

Breeders have always had to balance between stability and fragility. On one side, we want to preserve a distinct breed (for more about what that takes, please take a look at my interview with Dr. Lyle McNeal, a pioneer of sheep conservation, in my newsletter) – the structure, fleece, character and temperament that make a Border Leicester a Border Leicester. On the other side, there is a very real danger of breeding too closely for too long – loss of vigour, reduced fertility, smaller lambs, weaker immune systems and fewer options. That balancing act shows up in three terms – inbreeding, linebreeding and the inbreeding coefficient (COI).

Inbreeding means breeding closely-related animals – you know it when you hear it, there’s an instinctive ‘ick’ factor. Basically, the closer the relationship, the more likely it becomes that lambs will inherit the same version of a gene from both sides. What was hidden becomes expressed. . . As in the infamous “Habsburg jaw,” it’s not always pretty.

Linebreeding is a more controlled version. . . it’s the deliberate practice of breeding animals that share an influential ancestor – not always close relatives but connected enough you can reinforce a particular type. Linebreeding done well can stabilize traits – it can preserve excellence. Done poorly and it’s just gussied-up inbreeding, Habsburgs with a kick-ass PR team.

For small populations of endangered sheep, this is where it gets tricky. If you have an oops – and we have one in our flock, a charming youngster we called Lyle – and that oops becomes part of a breeding pool (Lyle had that temptation removed when he was 3-months old), a breeder doesn’t have unlimited unrelated stock to cross to fix the problem. The genetics are finite. Choices matter.

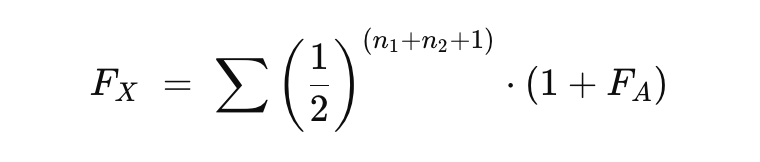

The tool we use to figure this out is called the Inbreeding Coefficent. It’s percentage that tells you how inbred the potential offspring is – it’s the siren that says “Yikes!” For most animals, 0-5 per cent is considered “low risk.” We strive to keep it under 6 per cent. Anything over 10 per cent and most authorities advise caution. Fortunately the math isn’t up to me – Mr. Galbraith didn’t cover this equation in my Grade 11 class – the Canadian Livestock Records Corporation can do it automatically.

Yeah, me either.

I was talking to a now-long-retired Border Leicester farmer a few years ago who told me that even though he loved the breed, “I never seemed to keep them much past 8 years-old.” This was a good shepherd who took great care of his sheep. But this anecdote is also telling – longevity and long-term resilience are often one of the first ways we can tell an animal’s ancestors may have been too closely connected for too many generations. In a colourful turn of phrase, “Too many people, not enough last names.”

I’m not an expert in breeding but once I decided to take the plunge, I wanted to make sure we could do it as well as possible. There are so many variables and naturally, most of my emotional labour was spent on the what-ifs of delivery. Sticking your gloved (if you have ‘em) hand into another female’s vulva is an intimidating prospect. Doing it when you’ve had the stirrup experience yourself brings a primal empathy along with it. Paying attention to genotype and phenotype, planning for best outcomes in advance and being careful and thoughtful about our breeding pairs can reduce the risks in this department as well.

Breeding season takes a lot of bandwidth. It’s a heckuva lot more than just “letting the ram in.” Banjo – bless him – is not blessed with any more brains than he needs to get the job done. Someone has to do the thinking around here and when it comes to the future, it’s my responsibility to make sure the foundation for our house is strong, the walls are straight and true and everything is plumb. When that’s done well, the risk of future complication – water in the basement, rot under the deck, damage to the joists – become a lot less likely.

If you’re interested in subjects like these there are more resources on our Keeping page, under Farming Practice and Animals and Breeds.

This is a Living post, a post to share my thought processes, where my priorities for breeding and lambing lie and the philosophy that underpins our activities here at the homestead. It is not a how-to, “expert advice” or meant to reflect a wider experience than just my own, on my farm, here with my sheep.

If you’re interested in our day-to-day process, a lot of that will be in an upcoming Tending post as we get closer to Baby Day.

Leave a comment