What would you do if you discovered a family heirloom proved your ancestors were doing hundreds of years ago exactly what you’re doing today?

Unlike so many of the people who have guided me along on my sheep adventure, I didn’t grow up knowing I came from shepherds.

I did grow up knowing I came from women who knew how to make do. Women like all the many Christinas – my family has a lot of Christinas – who sewed, mended, grew, cooked from scratch and could stretch a dollar until it screeched. That kind of inheritance is obvious – it lives in our hands.

But this one? Well, for this one, the story was woven in wool.

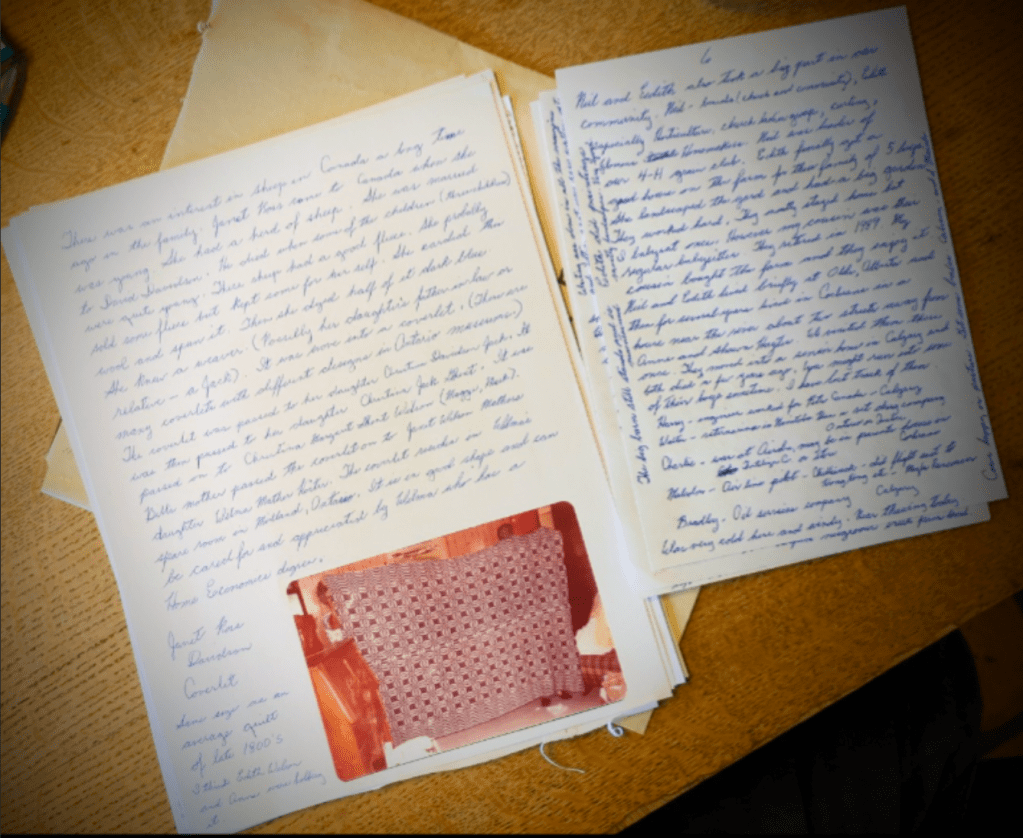

A family coverlet resurfaced in recent conversations between myself and one of my mother’s many (many many) cousins. Cousin Audrey lives in Saskatchewan, from the family of my Grandpa’s oldest sister, Maggie. This coverlet has been passed down through that family for more than six generations now and currently resides, beautifully draped and folded, in my cousin Wilma’s home in Ontario. It’s a thing of beauty, a heavy, indigo-and-natural cream blanket, woven in an overshot pattern called “Orange Peel” (thank you to Mackenzie Kelly-Frére for the identification). It was woven in two strips, sewed together along the length of the selvedge.

And the woman at the beginning of the coverlet’s story was called Janet Ross, an immigrant from Dunblane, Scotland. And for Janet herself, her family story was wrapped up in the sheep that rambled and grazed around Stirling Castle.

Janet Ross brought that love of sheep with her to a new world when she arrived in Canada all those generations ago. In the world she built for herself in Lanark County, Ontario, Janet included sheep. Not in the “there were sheep around the farm” sense of sheep, she had a flock of her own, a flock she managed and tended with all the knowledge generations of Highlanders could bequeath her. She managed wool and processed their fibre. She had enough skill and knowledge to card, dye and spin the yarn into a coverlet that’s still alive today. That makes her, in every meaningful and historical sense, a shepherd.

A woman, a flock, a life

In early settler Ontario, sheep were not a hobby, they were infrastructure. Wool meant blankets, clothing, trade goods and household security. For Janet, widowed with young children at home, sheep were manageable livestock – small, hardy and convertible into food, fibre and cash. They fit the scale of labour in a world that didn’t give women legal or economic power but depended on their productivity anyway. So she kept them, worked the wool and turned the fleece into something that outlasted her.

What kind of sheep did she keep?

Naturally this is a detail I want to know – unfortunately, there’s no documentation to tell me. Still, I can guess at quite a lot even if the paper trail is non-existent. Janet came from central Scotland, an area of the country that fostered hardiness in the animals as well as the people. In that region, the sheep were most likely either Cheviots or the ancestor of today’s modern Scottish Blackface – tough, adaptable and used to rough forage. By the late 1700s/early 1800s, another breed had started to make inroads into the region, from just south of the border in Northumberland. Bigger, with longer wool better for meat and fleece, this new breed was being crossed on to the Cheviots and Scottish Blackface to give Highland shepherds hardiness, size and wool strong enough to support the growing textile factories of the Industrial Revolution. This particular cross was so successful that these foundation breeds were sent to the New World, to the small farms and homesteads of Upper Canada, to provide the raw materials pioneers needed to thrive.

That breed was the Border Leicester.

I KNOW!!!!! Right????

The Pattern, the Colour and the Auld Alliance

Like many traditional patterns, Orange Peel gathered stories as it traveled throughout the new world and the old. Some North American weaving and quilting folklore links it with the Marquis de Lafayette, the French general who essentially won the American Revolution (yes it is true. Look it up). Whether that association can be historically proven or not, the idea endured – a floral, radiation pattern tied to France, woven into household textiles.

And then there is the colour. . . Deep blue, likely indigo or possibly woad. Both were practical and common, yes. But blue is also the colour of a French soldier’s coat.

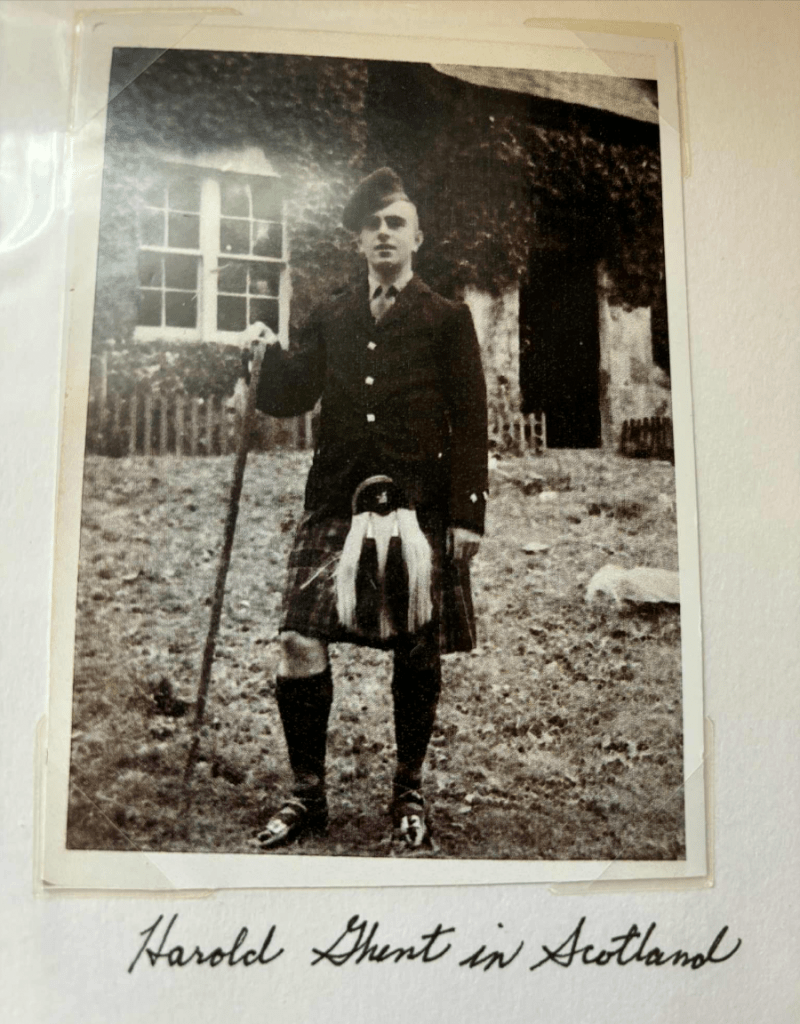

Janet Ross came from the Highlands and the Scottish Highlands have a long memory. Even after generations, my dear Grandfather Harold, Maggie’s little brother, could get into his feelings about the Campbells – “If only the ships had come from France!”

The Auld Alliance, the centuries-long bond between Scotland and France shaped politics, loyalties and cultural identity well into the Jacobite era. Even after the battles were lost and the last pibroch faded from the glens, those affiliations lived on in story, song and sentiment. It lived in displacement and outlaw proscription, in sectarianism and lines drawn through communities. It was encoded in the clothing, in which church you went to, and in rural Ontario, on which concession you lived.

Janet would settle in Lanark County, a corner of the province where Scottish and Irish immigrants carried their identities and their cultural wounds into the fabric of daily life. Loyal Orange Lodges, King Billy parades and other identity flags shaped communities for generations – Grampa Harold recounted many stories of mischief conducted after dark (and occasionally in broad daylight) between communities.

Against that backdrop, a Highlander woman designs an indigo coverlet in a pattern linked, however anecdotally, to France. It’s a story with layers of resonance, more than a whiff of mythology. It’s not a statement or a flag but it is a reminder than textiles hold threads of life, of history, identity, morality, politics, religion and resilience. People adapt, emigrate, intermarry, raise children, bury each other and survive. The deep currents of memory – who was our ally, who was our enemy, who was kin to us – don’t disappear. Like the helix of our DNA, they endure in one form or another. Textiles tell the tale, sometimes in the threads of a coverlet.

On kinship

I raise sheep now.

Now it’s me out here day-after-day, wandering around, noodling about pasture height and mineral balance and parasite cycles. I argue about wool markets and Canadian fibre infrastructure. I stand in fields with greasy, lanolin-smeared hands, hay in my hair, shit under my nails and wonder how on earth I got here.

. . .But maybe I didn’t “end up here.”

Maybe, just maybe, I came back. Back to land, back to sheep, back to Janet. Long before there was a homestead with a name, before there were spreadsheets and grazing charts and assessments of any kind, there was a woman standing on a patch of ground in Lanark County, Ontario surrounded by her own small flock and nothing much more than a stubborn determination to keep her family clothed, fed and warm.

I don’t know if Janet called herself a shepherd but the wool in that coverlet draped so beautifully in Wilma’s spare room says she was. Somehow, don’t ask me how, across generations of daughters, granddaughters, cousins and sisters, an army of women kept homes running on grit and grace and skillful knowledge. . . an orientation toward sheep, fibre, resilience and usefulness. It’s all found its way to me on my windblown patch here on the Alberta foothills.

The coverlet is there. The sheep are here – and I am beginning to understand that this life may not have just been something I chose. Possibly it’s something I inherited, a life I’ve stepped back into. For Janet, it was survival. For me, survival of a different kind.

But any way you look at it, a shepherd.

To find more resources related to textile history, weaving, craft and more, check out Keeping, Craft and Material Culture.

This is a Living post, a post to share my thought processes, where my priorities for breeding and lambing lie and the philosophy that underpins our activities here at the homestead. It is not a how-to, “expert advice” or meant to reflect a wider experience than just my own, on my farm, here with my sheep.

Leave a comment