Small farms can’t compete on scale, we must compete in our capacity to adapt. What happens when we prioritize resilience over efficiency?

On March 21, I will shear sheep.

Some of them anyway. It’s unlikely all of them will feel the whirring buzz of Alex the Shearer’s handpiece. And make no mistake, that’s an intentional choice, I am choosing to have to pay twice for shearing in a single season. I am prioritizing repetition and redundancy. Believe me when I tell you, while that distinction feels small when you read it here on a screen, in practice in our current culture of Ag, it represents an entire philosophy – counter-cultural, rebellious and about as punk rock as it’s possible to be, wearing my poofy, patchy, cozy-warm coveralls.

Betcha didn’t know that about your friendly neighbourhood shepherd, didja? O yes, I am a fan of the genre, a fan of the ethos behind it. One of these days we’ll sit down and hash out the virtues of the Stooges, DOA, Nick Cave and more. But for right now, let’s get back to the sheep.

Shearing Day is circled on the calendar. It’s a Saturday, the entire day is given over to opening our gate and letting our guests come in, learn, work, talk and build community. Alex the Shearer is booked, the mill is waiting. The ewes are roughly one hundred days bred. We will assess body condition, trim feet, vaccinate.

Late March in Alberta can be forgiving or horrifying — sometimes on the same day. For this rust belt refugee, Alberta’s meteorological volatility is migraine-inducing, literally. Trying to keep tabs on weather requires no less than four weather apps on my phone and sometimes, all those conflicting forecasts can offer me is the chance to pick the one I hate the least.

Making Wise Choices, Choosing Good Consequences

In the sheep paddock, I have mature ewes in good body condition, a handful of yearlings still growing into themselves, a few that are carrying a little less flesh than I would prefer. I have deep bedding, multiple hay lots, barley grain, shelter, heat lamps if absolutely necessary.

I have options.

If I prioritized efficiency, I’d call Alex, book the day, shear the sheep and move on to the next item on my seasonal to-do list. Neat, clean, done.

Efficient systems prefer clean lines. They prefer uniformity, standardization, completion in a single sweep. There is comfort in finishing a job in one pass, it makes life in that context look ordered, “professional” (whatever the hell that means) and the human involved gets to feel virtuous in terms of productivity and competence. What’s not to like?

But resilience rarely looks orderly. Resilient systems don’t prioritize the same way, they don’t ask the same questions, they don’t have the same goals and so – obviously – the tools look very different.

Instead of asking, “What is the fastest way to do this?” resilience asks, “What allows this system to adapt to the unexpected?”

Alberta is Weird

If Alberta has taught me anything, there is no such thing as no surprises, alas. I could wish otherwise but I am a realist – I must live in the world as it is.

Come late March, we could be basking in soft sunshine and squelching across thawing ground. Just as possibly, we could be gritting our teeth and squinting through sideways snow and a screaming north wind. Maude, a ewe in body condition 4/5 will tolerate a cold snap differently than Castor, still allocating energy to growth. Lucy does not care that the calendar says it is Shearing Day.

My sheep have their own ideas about so many things and no matter how carefully I go over The Plan, they don’t seem to care. If they did, Lizzie and Charlotte wouldn’t have presented me with surprise babies in 2025. I may be a lot of things, God help me, but I am disinclined to forget the depths of my shocked surprise and then the intense effort that came after. No, surprises, if at all possible, must be accommodated before they show up. I like a plan. If nothing else, it’ll give me something to throw out the window later.

But back to Shearing Day. The mature, well-conditioned ewes who can tolerate the metabolic shift will be brought to the board for their pas de deux with Alex, my favourite shearer, twirling around them until the fleece peels away in a complete and single piece. I will leave the yearlings in their wool, deferred to alpaca shearing day in April. For our newly-naked sheep, I will watch the forecast, adjust the feed. I will respond to the individuals in front of me rather than the abstraction of “the flock.”

This is slower. It consumes time. It demands assessment instead of execution.

But crucially, it also strengthens the system.

Setting Our Table

I think often of systems as tabletops. Any human enterprise – farm, corporation, institution —operates on a surface with fixed dimensions. The tabletop does not expand just because we want it to, it’s finite. We may add more tables, but each individual surface has limits and it’s on that surface that we’ll work out our priorities.

When we pursue efficiency aggressively, it spreads across the table. It takes up space with procedures, targets, optimization, standardization – there is nothing inherently wrong with that, efficiency is not a villain. It is powerful and often necessary. Like the ubiquitous can of WD-40 in every workshop from here to Blacks Harbour, efficiency is the thing that makes the system move.

But the more surface area efficiency takes, the less remains for flexibility, redundancy, and nuance. There is less and less space for individual assessment, for adaptability. No space remains for slack . . . and slack is what absorbs shock.

In pre-industrial times, farmers understood this instinctively. They planted multiple crops. They kept varied livestock. They spread their risk across seasons and species and strategies. They did not optimize for the highest possible yield from a single source. They optimized for survival. They did this not because they were unsophisticated, but because they understood their constraints. They did not possess abundant land or capital. What they had in abundance was labour. In Dr. Jim Handy’s book “Tiny Engines of Abundance” (look for it on our Keeping page under Farming Practice), he points out that labour – or skills – allowed these yeoman farmers to diversify. Labour allowed them to hedge against war, plague, drought, or flood.

Adapt to Survive

Small farmers today face a similar equation. We can’t compete on scale, we must compete on adaptability, on our ability to absorb surprise. That resilience costs time and time must be given space on the tabletop.

When I worked in oil and gas, there was a word the corporate wonks liked to trot out – nimble. They wanted the company to be nimble. It sounded modern and responsive but nimbleness without slack is illusion. If every inch of the tabletop is dedicated to production, there is nowhere to place surprise. And when surprise arrives – usually in a messy splat – something gets pushed off the edge.

Sometimes revenue crashes to the floor, sometimes morale. In agriculture, unfortunately sometimes it is animal health and sometimes it’ll be the farmer.

Pick Your Placement

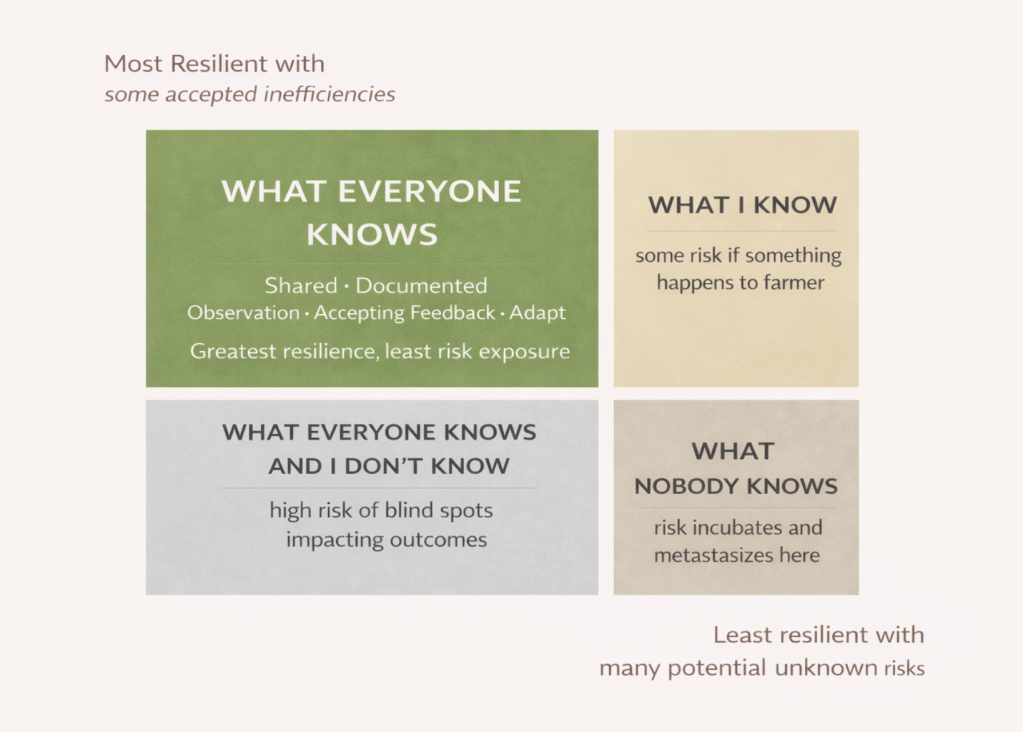

I find it helpful to divide the tabletop into four quadrants, much like the Johari Window (and yes, all you survivors of too many corporate HR confabs, stay with me — I promise this isn’t heading toward trust falls). The quadrants are simple: what I know and everyone else knows; what I know and no one else knows; what everyone else knows and I don’t; and what no one knows. A resilient system pushes as much as possible into the first quadrant — shared knowledge: clear criteria, visible trade-offs, documented reasoning, observation, accepting feedback and adaptation — what we all know.

When too much resides in “what I know and no one else knows,” the system becomes dependent on one person, a cult of personality. When blind spots accumulate in “what everyone else knows and I don’t,” fragility compounds. And the quadrant of “what no one knows” is where shock and risk incubate and metastasize.

Efficiency can operate in any of these quadrants, just as resilience can. The difference lies in what we reward. When efficiency becomes the goal rather than a tool — when it becomes the primary metric because it ties so neatly to money and money fits obediently into tidy spreadsheet cells — the system begins to shift. Decision-making narrows and information concentrates. More and more moves out of “what everyone knows” and into smaller, more opaque spaces. With all eyes fixed on productivity, resilience quietly loses ground until, without much fanfare, it slips off the table entirely.

Choosing to shear some ewes and not others is inefficient. It may mean poor Alex must endure my company once again but he’s usually pretty tolerant. Choosing to shear – or not to shear, that is the question (sorry!) – is an intentional allocation of space on the tabletop. I’m choosing choice, I’m choosing to assess, to adapt, to take consideration. I’m choosing nuance. My decision acknowledges that individuals matter, that Charlotte is not Amy is not Lyle, is not Lois. It acknowledges the obvious – weather matters. That body condition matters. That gestational stage matters. That revenue matters, by god and that at the end of the day when my head hits the pillow, my own peace of mind matters.

It accepts that resilience requires nuance.

And nuance requires time.

No Binaries, Only Spectrums

Any move to prioritize resilience will decrease efficiency. No getting around it, the job will take longer and the decisions aren’t predictably uniform. As a result, the outcomes are messier. But the system gains something far more valuable than speed: the capacity to bend.

Black-and-white thinking is seductive because it simplifies the surface. Either shear or don’t. Feed high or feed low. Either diversify or specialize. Binary, either/or decisions feel decisive. They present the table as ordered, linear and easy-to-understand.

But living systems resist binaries. They operate in gradients, spectrums and probabilities. They require us to hold multiple truths at once: efficiency is useful; resilience is protective; labour is finite; the tabletop does not expand.

So my real question is always the same: what do I want occupying this space? What’s going where on the table?

On March 21, I will shear sheep.

Some of them.

And when I do, I will protect a revenue stream, prepare for lambing, respect the variation within my flock, and preserve options for whatever Alberta decides to deliver next.

But seriously. Go home, Alberta. You’re drunk.

Nick Cave at his not-so-terribly-long-ago concert in Vancouver. Outstanding. And the people watching was spectacular.

This is a Living post, a post to share my thought processes, my experience and the philosophy that underpins our activities here at the homestead. It is not a how-to, “expert advice” or meant to reflect a wider experience than just my own, on my farm, here with my sheep.

Leave a comment