How does barley straw impact feed and hygiene?

If you ever visit our place in winter, you’ll notice something almost immediately: we use a lot of barley straw.

Not just a little “sprinkle for bedding.” Straw is a structural element in our winter system. It’s part of how we keep the flock comfortable, how we keep our barns clean, and how we keep our hay costs from getting silly during cold snaps. It’s bedding, yes — but it’s also nutrition-adjacent. Or perhaps more accurately: it’s rumen-adjacent.

On a farm where winter is a long season and hay is expensive, the question becomes: how do you feed well, keep animals warm, and avoid both waste and constant ration tinkering?

The best answer I’ve found is barley straw.

Our straw is local, and that matters

We’re lucky: our barley straw comes from a local farmer about fifteen minutes driving time north of us. It’s the kind of small detail that makes a big practical difference. We’re not hauling it from far away, we’re not paying “boutique straw” prices, and we can get it reliably.

Over the past few years, conditions have tended to be dry at harvest time. That affects straw quality in a way that you might not expect if you’re picturing straw as rigid yellow sticks. . . Yerg.

Fortunately for my sheep and their much-softer-than-a-cow mouths, when barley is harvested very dry, the stems tend to shatter. They break into shorter, more manageable pieces. That makes the straw a lot more attractive to the flerd, because it’s easier to eat — less of the “long, poky, not worth it” factor. They can chew it instead of flossing with it.

And every once in awhile, they hit pay dirt. Sometimes Roy’s combine misses a bit and some barley seed heads make it through into the bale. When that happens, it’s basically Christmas. You can feel the mood in the pen shift. The flock isn’t just bedding-digging — they’re treasure-hunting like a bunch of wooly truffle hounds.

That right there is a good day.

Straw does something hay can’t

Hay is our main winter feed – you can read all about our hay in another Tending post about hay analysis. But hay is expensive, and it’s too costly to provide unlimited free-choice hay all winter. I feed hay in amounts that make sense for the animals and the conditions, and then rely on straw to do the rest of the job that winter demands.

And that job is easy-peasy, in theory — we have to keep those rumens running. (I swear, Steppenwolf has been playing on a loop in my head since this morning.)

Sheep don’t just need calories in winter — they need fermentation. A functioning rumen is a heat source. In cold weather, one of the worst things that can happen is an animal going too long without fibre moving through the system. You can’t keep warm on an empty tank.

Barley straw is not “high nutrition.” It’s not meant to replace hay. But as a free-choice option it provides:

- constant fibre

- constant chewing

- constant rumen activity

- constant heat production

In other words, barley straw gives sheep and alpacas a way to regulate warmth through rumen function without requiring us to double the hay ration every time Alberta decides to throw her meteorological weight around.

An important caveat: heritage breeds, like our Border Leicesters, tend to be hardier than many highly-specialized modern breeds. Think of genetics like a tabletop — the more real estate you dedicate to a specific trait (like having a lot of lambs at one time), the less room there is for things like hardiness or wool quality. That’s not a dig against the modern breeds, that’s biology. Border Leicesters are generalists — they do a lot of things reasonably well (like hardiness) but can’t compete against modern breeds in those breeds’ specialties. I can swim pretty well. . . but I’m never going to be Summer McIntosh. On the other hand, I bet Summer can’t tip a sheep, so there’s that.

Barley straw, for our sheep in our context, are an economical tool for a biological need.

And yes: they actually eat it

This is the part that surprises people who assume straw is only bedding.

Our flerd eats it — enthusiastically at times — especially because those shattered stems make it easier and more appealing. Straw isn’t just something they lie on; it’s something they pick through, nibble, and snack on throughout the day and night. If we’ve ever had guests who feel concerned that we’re “feeding straw,” I always want to say: no — we’re feeding hay. Straw is simply what keeps the internal furnace humming steadily instead of sputtering.

It’s not a replacement. It’s a buffer.

Straw is also the bedding — and housekeeping matters

Here’s the other job straw performs: it creates a dry, insulated base layer that protects the flock’s energy budget.

A winter animal can be well fed and still struggle if it is constantly losing heat through damp, cold ground contact. Deep bedding reduces that heat loss. Dry bedding reduces the risk of foot issues. Clean bedding supports general health and comfort.

So yes, straw is our bedding, and we take the bedding seriously.

Our routine is simple and relentless:

- we spot clean daily

- we do a bigger shed refresh roughly once a week

(more on that in another post — housekeeping is its own subject)

But here’s the important part: the schedule has to stay flexible, because we aren’t managing one species. Just like sheep aren’t little cows, alpacas aren’t very sheep-like at all in one very important respect.

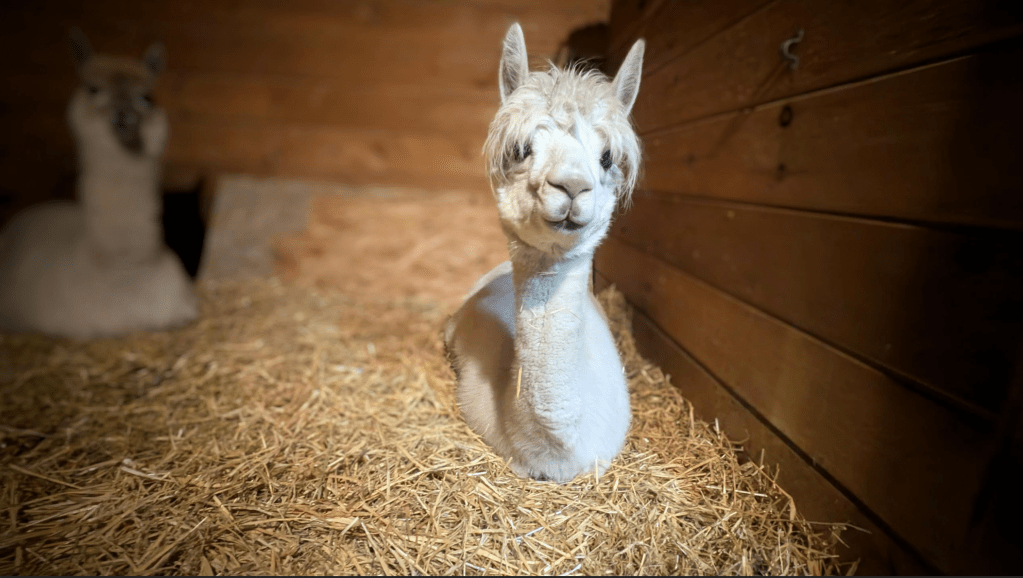

Mixed flerd reality: alpaca middens change everything

Alpacas have their own charming and very specific housekeeping habit: they create middens. All the girls go to the same loo at the same time, just like a bunch of middle-schoolers. It means I don’t have to go very far to find the mess I’ve got to clean up but it does mean that those spots – and they are legion – tend to get pretty friggin’ damp.

With a mixed flerd, the bedding refresh schedule can’t be dictated by the calendar alone. Once-a-week is a baseline but alpacas can force an earlier refresh depending on how they’ve decided to arrange their bathroom real estate. If the girls – Freya (AKA Warrior Princess Queen of the Damned), Susie, Daz, Jubie and Baby Sundae – have been bunking inside, chances are our daily cleans are a bit more extensive. Those girls like to be inside to poop and are about as open to sweet reason as the tide. When the sheep get pushed to the perimeter because our alpacas have been standing spaddle-legged at centre stage, that’s the first sign that the bedding is going to need some attention.

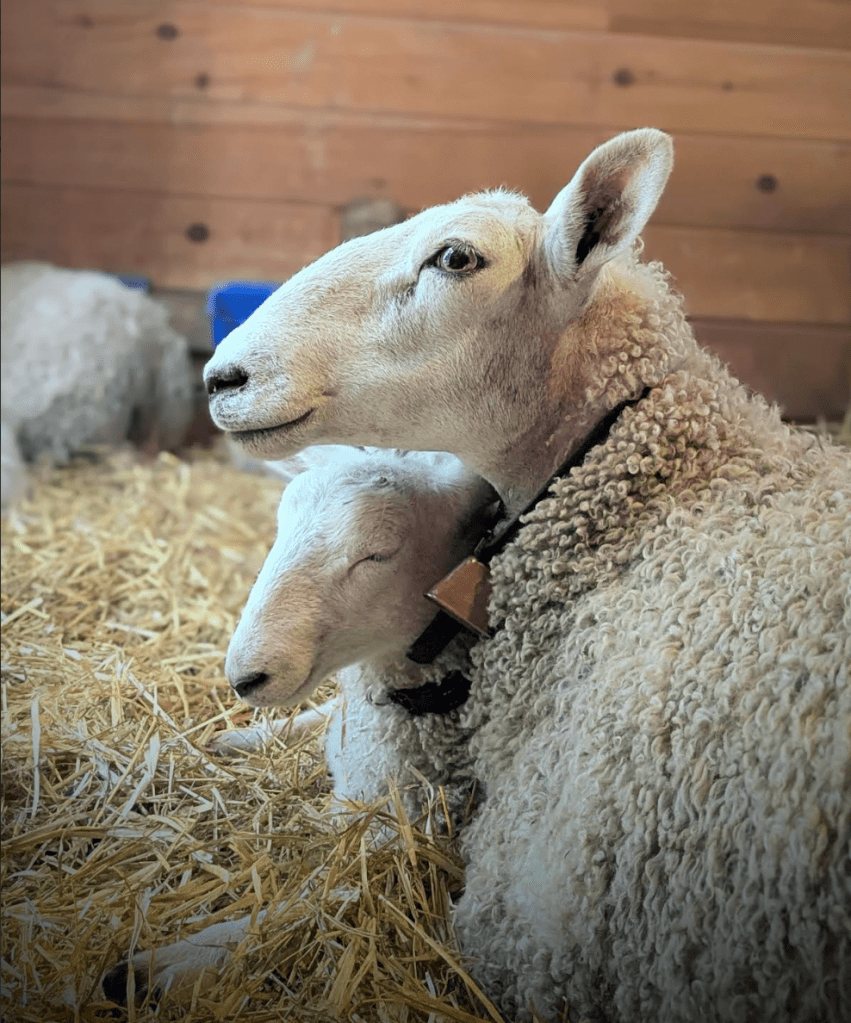

“Fresh sheets,” according to sheep

One of my favourite things about winter livestock is how blunt they are. Sheep are not subtle about comfort. When bedding is fresh, they sink into it with obvious satisfaction — they look like marshmallows floating in a mug of cozy cocoa. When it isn’t, they start avoiding certain spots. When the sheep get picky about where they bunk, it’s for a basic reason, the straw is icky and it needs to be dealt with. They’re asking for fresh sheets.

The mucky-knee indicator

There’s another sign that’s almost comically practical, and once you know it, you can’t unsee it: mucky knees. It’s particularly easy to see with Border Leicesters — they’re white and their legs are free of wool.

Sheep get up using their front knees. When bedding is clean and dry, those knees stay clean. When bedding is damp, stained, or overdue for refresh, you’ll start seeing sheep with wet or dirty staining on the knees of their front legs.

If you see mucky knees, it’s usually time.

It’s an easy animal-based metric — and I like metrics that don’t require a clipboard.

Straw: the winter ingredient that does double duty

So barley straw does two major jobs for us:

First, it provides an economical source of fibre that keeps rumens active and animals warm, particularly during temperature swings and cold snaps.

Second, it provides deep bedding — the physical insulation layer that keeps animals dry, comfortable, and energetically efficient through the winter.

And the best part is that it fits the scale of a real farm. It doesn’t require a complicated ration. It doesn’t require expensive inputs. It just requires good access to straw, good storage, and the willingness to keep up with bedding management.

On our farm, barley straw is one of those quiet, unglamorous farm tricks that makes winter work.

This is a Tending post — a practical look at our methods, routines, and on-the-ground decision-making with the flock. It’s not a one-size-fits-all how-to, and it isn’t meant to substitute for local knowledge or professional guidance. It’s just what we’re doing here on our farm, in our conditions, with our sheep (and alpacas), written down plainly in case it helps. For more about why we do things the way we do them, the philosophy that informs our process, you’ll find those posts in Living.

Leave a comment