Is hay a fallback? Or an integral part of your SUMMER feeding strategy?

There’s a quiet assumption in livestock culture that grass is success and hay is compromise. Particularly in the regenerative agriculture space, there is a sense that if one resorts to hay, it’s a management error.

But that only makes sense if we think of hay as what you feed when pasture runs out.

I don’t.

For me, hay is not a fallback, hay is a strategic tool and like any good tool, it’s useful in more than one season. Let’s be super-clear and intentional – hay is just harvested sunshine, preserved and fed out when conditions warrant. Nothing more, nothing less. In this way, the decision to feed hay is based not on some arbitrary or short-term version of success but rather on long-term observation, discipline and feedback from the environment.

Hay Feeds Animals — But It Also Feeds the Land

Yes, hay feeds horses, sheep and alpacas. That part is obvious.

But feeding hay also allows me to make decisions that protect pasture health and long-term productivity. Hay feeding can:

- Protect frozen or saturated soils from hoof damage

- Allow plants to rest fully and rebuild root reserves

- Concentrate manure and fertility where it’s needed

- Build ground cover from wasted stems and leaves

- Extend pasture recovery periods beyond what grazing rotations alone can achieve

In that sense, feeding hay is sometimes the most pasture-protective choice available.**

Hay Has a Role in Summer, Too

Here in Canada, we tend to associate hay with winter. But summer hay feeding can be just as defensible — sometimes more.

During drought or extreme heat, grazing can do real damage:

- Plants are already stressed and regrowth is slow

- Root systems are living off reserves

- Hoof pressure on dry soils can reduce infiltration

- Sheep in heavy fleece can struggle in open, exposed pastures

Feeding hay in shaded or controlled areas can:

✔️ Reduce grazing pressure on drought-stressed vegetation

✔️ Protect plants during their most vulnerable period

✔️ Keep animals near shade and water

✔️ Allow longer pasture rest so grasses recover fully

Summer hay feeding is not “giving up on grass.” Sometimes, feeding hay in the summer is choosing to protect future grass. In permaculture specifically, there is a philosophical emphasis on planting and tending today for yields we as land stewards may never see. We must think in terms of decades and centuries when it comes to our land management strategies, not just in seasons.

** Now there is one proviso that’s significant but may not be applicable across the board. Here at the homestead we’re really lucky to have approximately half our property in native grasses and other plants. I am crazy passionate about maintaining this important ecosystem and so we do NOT bale feed on native stands. We want to make sure we’re not introducing any of our tame grass species (Kentucky blue grass, timothy or smooth brome) into this delicate and vanishing world.

Hay as a Parasite Management Tool

Another quiet benefit for summer hay feeding programs: time.

Internal parasite cycles depend on animals re-grazing contaminated pasture before larvae die off. By feeding hay and extending rest periods:

- Pastures stay ungrazed longer

- Larvae die before animals return

- Reinfection pressure drops

The vast majority of parasites that affect sheep are not visible to the naked eye. I’ll talk about what we do for parasitism in another post – it really deserves its own article – but specifically where hay is concerned, feeding can buy enough recovery time to support animal health without chemical intervention (now of course, this all presupposes a high level of hygiene in the flock’s environment. Additionally, in Canada we’re fortunate to be mostly frozen solid for eight month, generally a time of relatively low parasite concern). This way, hay becomes part of a whole-system strategy, not just a feeding decision. For many shepherds, dealing with internal parasites is among the most expensive and labour-intensive processes on the farm. Having done it a few times myself, can confirm.

Flexibility Requires Preparation

Using hay strategically only works if hay is actually available.

So I changed how I buy it.

1. I Always Test My Hay

Absolutely foundational – guessing at nutrition is not a plan. A forage test tells me:

- Protein

- Energy

- Fiber

- Mineral balance

(For more about how I read a nutritional analysis, you can check out this post.)

Knowing what I’m feeding lets me adjust grain (if I’m using them), minerals, or access to pasture accordingly. It also helps me match the right hay to the right class of animals – different life stages have different intake needs.

2. I Keep at Least Six Months of Hay On Site

This is both practical and financial.

It gives me a buffer if:

- Drought slows pasture growth

- Wet conditions damage soils

- Wildlife pressure makes certain areas unusable

- I need to extend rest periods for plant recovery

It also protects against price spikes because hay markets swing wildly year-to-year. When I started this adventure back in 2018 or so, a 1200 lb round bale cost $80/ea, delivery included. Now, I’ll pay anywhere from $125 to $180/bale, small square bales (generally 50 to 65lbs each) are even more expensive – it’s up to each farmer to work out if they can usefully benefit from tractors or other kinds of mechanical feeding assistance generally needed for using round bales. Being smaller, small squares are easier to feed out by hand but costs can add up fast – one small square is approximately 102 per cent more expensive than the same weight of hay off a large round (assuming the small square is $13/55lbs and the big round is $140/1200lbs). That’s a helluva hit so spreading those costs out just makes sense.

And there’s another benefit – one that might not be quite so obvious. Buying during hay producers’ slower seasons helps build relationships and reliability. Hay sitting in the shed is money that’s not in the bank, after all. I have several regular suppliers I work with and over the years, they’ve come to understand what I’m looking for. I may not buy as much as some of their bigger customers but I buy regularly and I buy when the other customers are already done their purchasing. As a result, they often contact me when they’ve got hay that tests out the way I need it. That matters in years when hay is scarce – we’ve built a relationship that works for both of us.

By growing my relationships with as much care as I try to grow grass, I’m making sure I’m as important to my hay guys as they are to me. This really pays off in those tricky years when the weather doesn’t cooperate. When no amount of money can buy hay that isn’t there, those personal relationships really become the most valued currency.

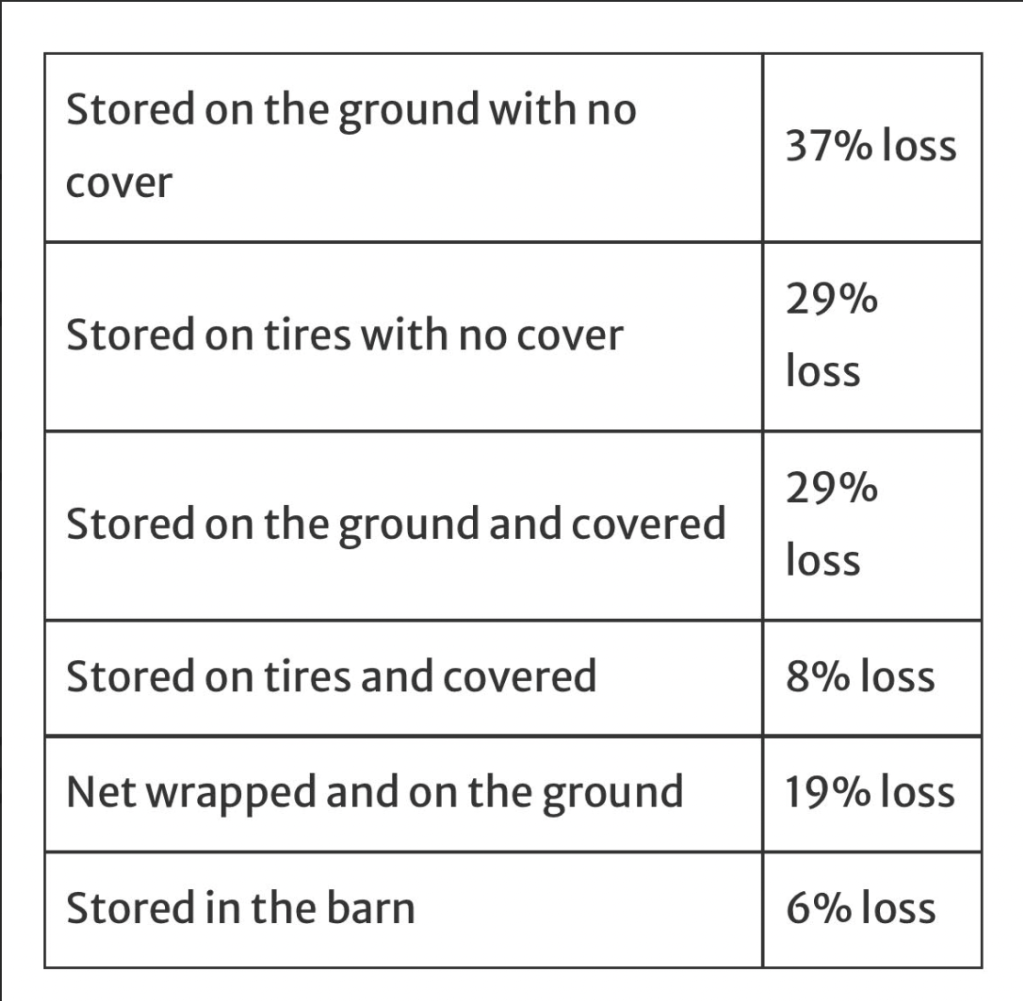

Here’s a handy chart that was shared with me by a feed nutritionist (thank you Abby!). If you’re going to keep hay onsite, the way you store it is very very important indeed. Proper storage will maintain excellent nutrition quality. We have some bales that have been stored in a three-sided shed for three years with no real loss of nutrition.

3. I Prefer Weighed Bales and Price-Per-Pound

Estimated bale weights are notoriously unreliable. Now, don’t jump to conclusions – most hay producers aren’t trying to shaft their customers. Hay that’s harvested in wet years is going to be heavier than hay harvested in dry years. That’s just biology. Hay that’s purchased after standing for a winter is going to be lighter as well. Depending on storage scenarios, nutritional value doesn’t always change but weight certainly does. But that lighter weight means I may have to feed more of it changing my cost-per-feed equation. That matters to me.

Most professional hay sellers are more than willing to get their bales weighed. In our area, producers have a cozy little arrangement with the local transfer station. If they know what their trailers weigh empty, it’s an easy equation to drop some bales on, get a new weight and do the math.

Buying by weight:

- Gives predictable feed budgeting

- Makes ration planning more accurate

- Ensures fair pricing for both buyer and seller

Nutrition may still be excellent after drying — but feeding days depend on weight. If a hay seller isn’t willing to weigh their bales, I keep looking.

The Hay vs. Grazing Decision

I don’t ask, “Should they be on pasture?”

I ask, “What does the land need right now?”

Here’s the framework I use:

| Condition | Best Choice? | Why? |

| Soil frozen or waterlogged | Hay | Prevents compaction and root damage |

| Early spring, grass just greening | Hay | Allows plants to rebuild root reserves |

| Drought or heat stress | Hay | Protects stressed plants and soil moisture |

| Parasite pressure high | Hay | Extends rest periods and breaks parasite cycles |

| Strong growth, adequate moisture | Grazing | Animals stimulate regrowth and cycle nutrients |

| Pasture ready, recovery complete | Grazing | Land can afford to give |

Hay feeding is not separate from grazing management — it is grazing management, just happening in a different place.

Stored Sunlight, Used With Intention

Like I said off the jump, I try to remember that hay is simply pasture harvested in another season. When I break open a round bale, I’m not stepping away from grass and it’s not some tacit admission of failure. I’m making a choice about where and when the flerd harvests sunlight.

That choice — made carefully — protects soil, plants, animals, and the farm’s future productivity.

I’m attending to what I think matters most.

For more resources on animal welfare, nutrition, hay feeding, pasture, feed analysis and small farms, check out Keeping, Farming Practice.

This is a Tending post — a practical look at our methods, routines, and on-the-ground decision-making with the flock. It’s not a one-size-fits-all how-to, and it isn’t meant to substitute for local knowledge or professional guidance. It’s just what we’re doing here on our farm, in our conditions, with our sheep (and alpacas), written down plainly in case it helps. For more about why we do things the way we do them, the philosophy that informs our process, you’ll find those posts in Living.

Leave a comment