There is a lot of knowledge to be gained by looking at hay. When you start to pull it apart, what story is hiding in your bales and how might it change or impact the way you use them?

You don’t need to know the Latin names, you don’t need a forage analysis, you don’t even need to be able to identify a single grass species.

You just need to look.

Hay analysis is a very useful – I would call it an essential – tool for feeding critters of all kinds (for more about hay analysis, you can read my earlier post on the subject). But back in Ye Olden Days, farmers did have other ways of making some judgments about hay that helped them to decide how best to use it. For those of us who make use of Adaptive Multi-Paddock Grazing (AMP – so much easier!) some of these older skills are just as useful today, although we’re deploying them for slightly different reasons. So let’s head out to the hay barn and grab some hay.

What do you see? I grabbed two different bales and picked through them very carefully trying to find a range of different plants. I made some judgements based on what I could see and then I had a conversation with the producer from each bale. Let’s see how I did, shall we?

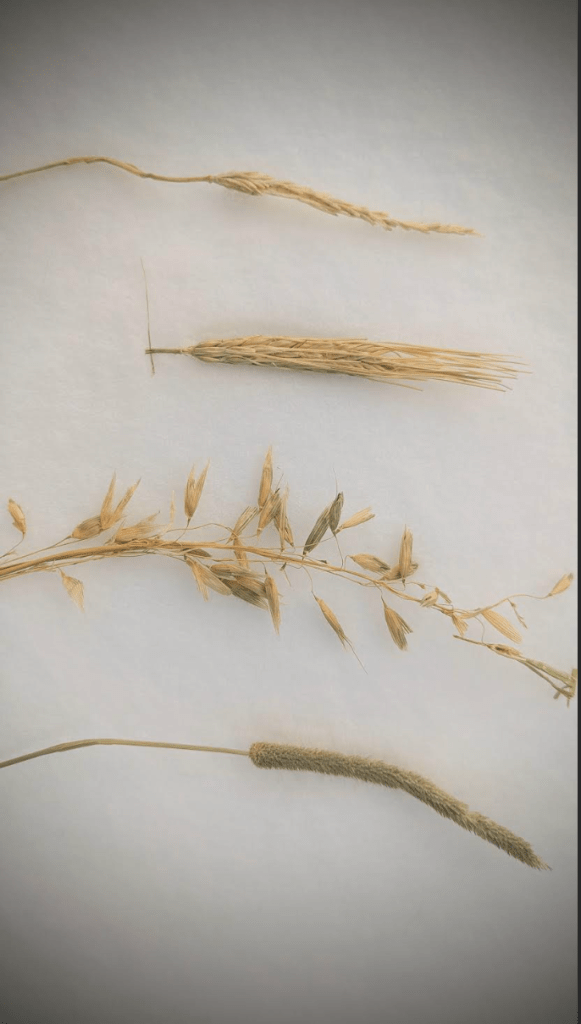

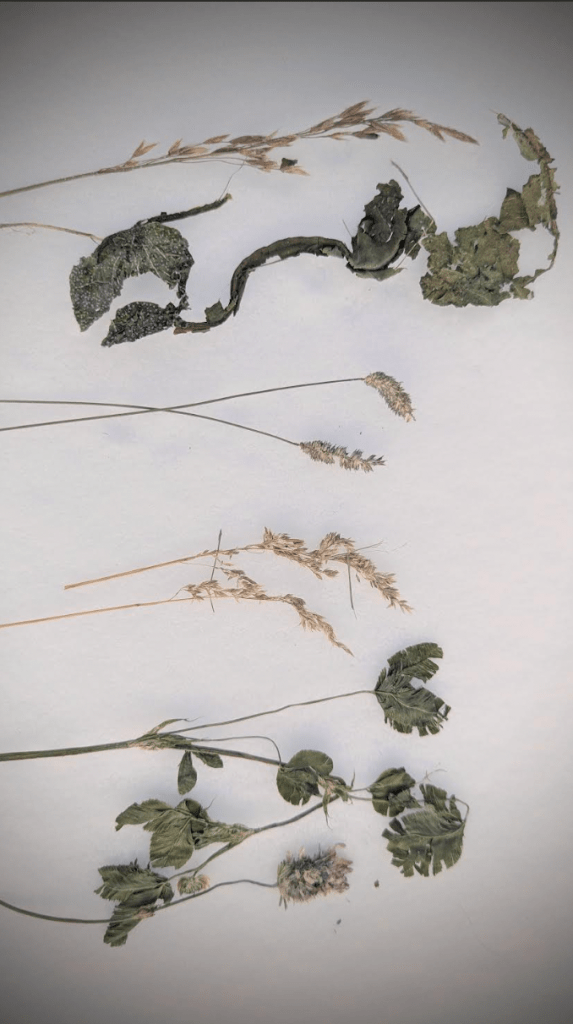

I started by laying out a few flakes of hay out on the snow. The white background makes it super-easy to spot differences and details. You can also do this on a tarp or the barn floor. Pull out stems at random and line them up. Then really see what’s there.

The very first thing I can tell you is that the total plant inventory is different – there are more varieties on right-hand sample than there are on the left. Additionally, on the right-hand side, there are two very distinct plant types – broadleaf plants, in this case, red clover and I suspect dandelion. Put a pin in that, it’ll be important later.

In sample A on the left, I have four distinct seed heads (seed heads are not by themselves always definitive – some seed heads from one species can look remarkably like a different species entirely. But that’s plant ID and that’s for another day). On the right, there are three distinct seed heads.

As I noodled on my two samples, a couple of things became clear to me.

First, Sample A on the left is a younger stand, likely converted from greenfeed relatively recently, likely managed with the usual conventional inputs (fertilizer and a topical herbicide application). I can tell that because there are no broadleaf plants in our sample. Herbicides often target these plants as weeds. I’m going to guess based on the size of the Timothy seed head (the one that looks like a bottle brush at the bottom of the photo) that fertilizer has been part of the field’s story at some point (Timothy seed production is very dependent on nitrogen levels in the soil). Sample B on the right is a much older stand, likely low input, likely managed with very little intervention of any kind and probably for quite some time. There’s Timothy in this sample as well but look at how much smaller those seedheads are. As well, the presence of clover and dandelion (presumably) tells me that herbicides were not used here and haven’t been for quite a long time.

I sent a note to both producers. Sample A producer came back to me – previously this field had been a greenfeed field and was only put to Timothy (a grass variety much beloved by horse people) last Spring. There was a lot of volunteer cereal grain plants coming up in the mix. This isn’t a bad thing at all – it makes my sheep behave like truffle hounds – and the energy those plants hold are much appreciated, especially during this colder weather spell we’re having.

Sample B producer told me that this field produced poorly last year (he was judging by the number of bales/acre), was at least 10 years old and hadn’t been treated with anything for something like a dozen years. The plants present in this bale – including the broadleaf plants – represent a field going through succession, that is, a field where the yield in plant mass is going down even as the variety of plant species (the biodiversity) is going up. Our soils in this area are naturally fairly low in nitrogen and this field’s progress through a succession period is obvious given not just the size of the Timothy seedheads but also the abundance of non-grass forbs in the sample. It’s as clear as the nose on my face. Which is sneezing. Yech.

Think about it like this

Just as fleece isn’t just wool, it’s the sheep, so a hay bale isn’t just feed, it’s a field.

When you bring a bale into your feeding program, you’re importing not just energy, protein and carbohydrates to get your critters through the winter, you’re also bringing in ecology, soil and seed. So what must you do?

Step One: Count the Differences

Start simple, start with seed heads.

How many shapes do you see?

- Panicle (open and airy, like oats)

- Comb (flat and tidy, like wheat)

- Brush (soft and cylindrical, like foxtail)

- Fan (sprayed, delicate)

- Tight spike

- Loose spray

You don’t need the names. Just count the forms.

Three different seed head shapes? Or six? Maybe more?

That number tells you something about biodiversity.

Leaves

Now look at the leaves.

- Broad or narrow?

- Flat or rolled?

- Fine like thread or thick like ribbon?

- Smooth or ridged?

- Hairy or glossy?

Again — count the differences. Uniform hay often looks… uniform. There will be a narrow range of leaf styles. By comparison, mixed hay will look a little chaotic. Note the differences – I use my phone camera for this. Look at the leaves and, if you can, look at the way the leaves attach to the central stem.

Flowers & Broadleaf Plants

Are there any?

- Clover globes

- Tiny sun-shaped composites

- Bells

- Purple, yellow, white, pink

- None at all?

A bale with zero broadleaf content tells you something while a bale with several tells you something different.

Step Two: What That Diversity Says About the Field

Once you see “different,” you can start asking why. As you get more adept at reading the hay, you’ll be able to see patterns and spot outliers, things that are really very outside what’s “normal” for your area.

Younger Stands

First-year seeded fields often look:

- Clean

- Uniform

- Predictable

- Limited in plant variety

That doesn’t make them bad. It makes them young and managed.

Older Stands

Ten-year stands begin to look:

- Mixed

- Layered

- Slightly unruly

- Less productive but more complex

And yes, yield often drops as diversity rises – that’s yield as measured in bales to the acre though, not in measurable nutrition. It’s important to understand why those yields may have dropped – more for the hay producer than for the hay customer – but one of the things I know is that succession directly impacts the volume of plants which is entirely normal and to be expected, it’s not a flaw in the natural order of life on grasslands.

Conventional vs. Low-Input Management

You can’t always know for certain. But you can infer.

Fields that are:

- Highly uniform

- Low in broadleaf plants

- Dominated by one grass type

Often indicate tighter management.

Fields that:

- Contain clover

- Show multiple grass types

- Include harmless “weeds”

- Feel structurally varied

Often suggest lower chemical input or longer rest between interventions.

This is not moral judgment, it’s just pattern recognition.

Wet Year vs. Dry Year

A wet year:

- Encourages lush growth

- Promotes legumes

- Softens stems

- Increases leafiness

A dry year:

- Produces shorter plants

- Tighter seed heads

- Less leaf mass

- More concentrated fibre

You can often feel the weather in the stems.

Step Three: What Happens When You Feed It?

This is the part many people miss. When you feed hay in a field, you are not just feeding animals, you are importing ecology. Now don’t light your hair on fire, we’re about to get controversial. You’ll be fine, I promise.

Herbicide Residue

This is controversial. It’s complicated. It’s debated but it is not imaginary. The longer-term presence of herbicides – like Glyphosate – in the soil is very dependent on the type of soil you’ve got. For some soil types, Glyphosate has been shown to remain measurably higher for longer than was previously thought.

If a field has been recently sprayed with persistent herbicides – and in Alberta, Glyphosate is used in hay fields very regularly – residues can pass through animals and remain active in manure. Those residues can affect:

- Sensitive legumes

- Garden soils

- Young broadleaf plants

Now, that doesn’t mean “never buy hay.” What it does mean is find your inner Olivia Benson and be prepared to dig in. It means:

- Know the field’s history

- Ask questions about inputs and how the field is managed

- Pay keen attention to what is in your hay bales

You can so do this.

Micronutrient Diversity

Different plants mine different minerals. Deep-rooted species pull from deeper horizons, legumes like clover and alfalfa fix nitrogen and broadleaf plants accumulate trace elements.

A biologically diverse bale feeds rumen microbes differently than a single-species bale and what passes through the sheep becomes soil amendment. Basically, diversity in = diversity out.

Seeds in the Bale

Every bale carries seed. As a land steward, the first question I ask myself is: “If this bale sheds into my pasture, am I going to be happy about it?” Ask anyone whose spent hours pulling out foxtail or Canada Thistle and you’ll already know why this is so important. We had strawberry spinach piggyback into some bales a few years ago and it has been the work of two years (and counting) to root out those things.

But it’s not always about controlling non-native invasives. Sometimes bale seed shedding is an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone – nutrition for critters yes, but while they’re eating, they’re also doing a little of what I call the 3Ps. Press, poop and pee. They press the seeds into the ground and then provide a little top-down fertility boost (sorry!) as they go about their business peeing and pooping. So what are our four-legged gardeners going to grow? What’s in the bale? Will they grow –

- Nitrogen-fixing legumes?

- Shallow-rooted tame grasses?

- Deep-rooted drought-tolerant species?

- Aggressive annual volunteers?

In horses, quite a lot of the seeds that get eaten will in fact grow in poop. For sheep and alpacas, this is less of a concern as most seeds don’t survive digestion. My flerd is a much more of a rootin’ tootin’ kinda gardening operation (Gawd. Someone stop me)

The essential thing to remember is that hay is a vector – it’s how plants travel. It’s also a medium – it’s where plants grow.

Soil Implications

Plant diversity influences:

- Root depth patterns

- Carbon deposition

- Water infiltration

- Fungal-to-bacterial ratios

- Soil aggregation

A mixed meadow bale feeds soil organisms more broadly than a highly uniform production bale. Again — neither is wrong, I want to be sure that everyone understands that. I make use of both types of hay but while I do, I recognize that they’re not the same and I treat them differently.

The Final Word

You don’t need a degree, you don’t have to be able to tell Smooth Brome from Meadow Brome. You don’t need to cart a microscope out to the hay shed – all you need is curiosity and two eyeballs. Lay it out, take a look at it, and start noticing what’s different.

How many different seed head types can you find?

How many leaf shapes?

How many colours?

That count alone tells you whether you are holding:

- A production crop

or - A biological community

Neither are “wrong”. Both have their place. When I stare at hay – which I do quite a lot – I’m trying to understand what I’ve got, where it came from and most importantly, what it’s going to do beyond feeding my animals. Hay analysis tells me precisely what I’m feeding my flerd. Hay observation tells me roughly what I’m feeding the land.

But they do different work.

Tending Is Paying Attention

When we buy hay, we are making decisions that ripple beyond the feed bunk. We are providing a stage for someone else’s soil story, we’re choosing an ecology to layer into our own land. Given what’s at stake, it’s important to lay it out, count the differences, ask about the field and figure out if what it does beyond filling bellies is a story you want to live with.

This is a Tending post — a practical look at our methods, routines, and on-the-ground decision-making with the flock. It’s not a one-size-fits-all how-to, and it isn’t meant to substitute for local knowledge or professional guidance. It’s just what we’re doing here on our farm, in our conditions, with our sheep (and alpacas), written down plainly in case it helps. For more about why we do things the way we do them, the philosophy that informs our process, you’ll find those posts in Living.

Leave a comment